Understanding Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement

And why more African governments need Security Sector Reform

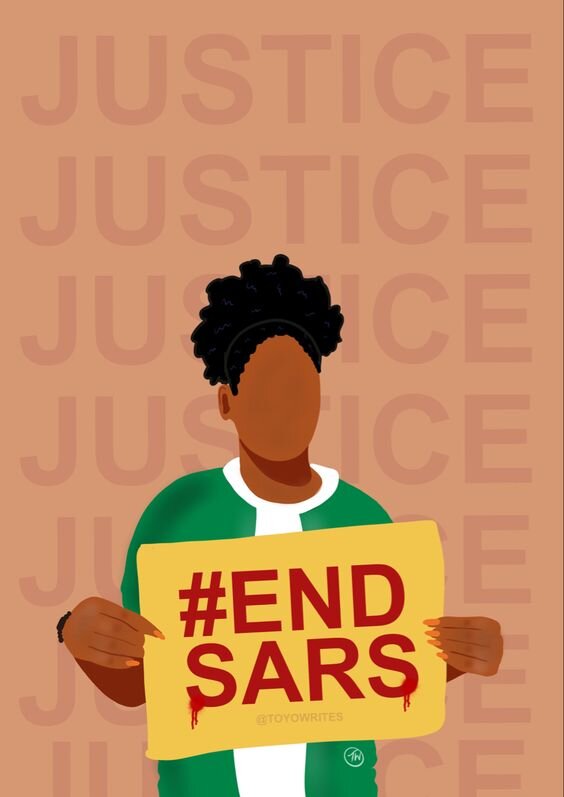

In early October, thousands of Nigerians took to the streets of Lagos, Abuja, and other major cities to protest against police brutality. They did that - in spite of the coronavirus pandemic to request for the abolition of the now dissolved federal Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). SARS was created in 1992 to tackle violent inner-city crimes but had been mired with irregularities and abuses. And most of the officers involved were never brought to justice despite Nigeria’s recently passed anti-torture law.

And as the protest grabbed global attention, and international personalities and activists posted the hashtag #EndSARS to show support for the movement, Nigerian security forces’ actions towards peaceful protesters remained violent. At one point, military officers - shockingly enough - openly fired on demonstrators, killing 11 people.

The security forces' use of deadly force to suppress the #EndSARS movement did not deter protesters from calling for police reforms. Which highlighted the Nigerian population’s strong desire for security reforms and effective governance overall

Moreover, for Nigerians, these protests are more than just about police violence. They are also meant to pressure the Nigerian government to tackle the increasingly high number of citizens living in poverty and youth unemployment that started before the coronavirus and have further deteriorated since the pandemic. And yet, the Nigeria government is doing little to address police brutality or the socio-economic crises, which will lead to more protests and instabilities.

Increase in Police Brutality During the Covid-19 Pandemic

In other African countries, similar uprisings against police violence have shown that African governments need to change the way they have enforced the recent Covid-19 lockdown measures. Cases of police brutality are on the rise, and sadly, some Africans would even suggest that policing on the continent is more deadly than the virus.

In Kenya, for instance, since the start of the lockdown measures, human rights activists have attributed the death of twenty-two people to Kenyan law enforcement.

For Ugandans, police brutality was a major public concern prior to the pandemic and the COVID-19 restrictions have only worsened Ugandan security forces’ appetite for excessive force. Their brutal actions have led to injuries and death of citizens caught violating lockdown measures. In one incident, a Ugandan vendor was severely injured when an officer implementing the measures intentionally kicked her saucepan filled with boiling oil towards her. And in November alone, 45 people were reportedly killed when Ugandan police attempted to stop protests that erupted after the arrest of presidential candidate Bobi Wine.

In South Africa, a country where the police are accused of killing up to 500 people a year, with no surprise, has also experienced an upsurge in police violence during the pandemic. In june, South African police’s lockdown enforcement resulted in the death of at least 10 people. In late August, tension with citizens heightened when police from Eldorado Park Station in Soweto shot and killed a young South African boy with down syndrome because he did not respond to officers’ questions.

This is why, even in the midst of the pandemic, Africans are peacefully pushing back against police brutality. Most of all, Africa’s peaceful movements have inspired, and are also inspired by the global Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality and systemic racism that started in the US after the killing of George Floyd, by Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin.

But so far, African governments have half-heartedly addressed police brutality. Some continue to use law enforcement as a way to maintain power and perpetrate violence. Ironically, similarly to how Western colonizers operated the security institutions during Africa’s colonial period.

Effective Policing is Critical to Peace and Stability in Africa

The African continent cannot achieve peace and stability without prioritizing security reform. As British philosopher Thomas Hobbes describes in Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme & Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651), a renowned book about political power: “there is unrelenting insecurity without a government to provide safety of law and order, and protecting citizens.”

In fact, in the past five years, there has been an increase in the number of serious conflicts, uprisings and protests on the continent, proving the absolute need for strong security infrastructures by the way of meaningful reforms.

How governments can address security issues

I believe that governments must first focus on ensuring accountability, oversight, and integrity within the security institutions. The United Nations (UN) Handbook on police accountability, oversight and integrity, states this can be attained through three overlapping priority areas: reducing corruption within the police; increasing public confidence by upgrading levels of police service delivery, as well as investigating and acting in cases of police misconduct; and enhancing civilian control over and oversight of the police.

More importantly, Africans also consider eradicating corruption essential to effective policing on the continent. A Global Corruption Barometer-Africa survey in 2019 in 35 African countries concluded that 47 percent of the participants believe most or all police in Africa are corrupt. The same survey disclosed that 50 percent of the African population believes that citizens can help stop corruption, which clearly shows Africans are committed to institutional reforms.

These reforms can only be achieved if African governments secure adequate funding for security institutions, which historically have been grossly underfunded.

Which also means African rights activists can not align with Western activists’ call to defund the police in the same way. Since most Africa countries’ security institutional problems mostly derive from insufficient funding and scarce resources.

Promoting Gender Equality in Law Enforcement

And at the top of the list--gender equality has to be the lynchpin of all security reforms. African governments must implement policies to promote gender equality and ensure the rights of women and other marginalized groups. Essentially, security apparatus must pay special attention to crimes committed against women, children, and LGBTQ+ people, and have to do more to reduce Gender Based Violence (GBV) which is prevalent on the African continent, as it is everywhere else in the world.

Studies even suggest that countries with high levels of national violence against women and girls are more likely to experience armed conflict than others. When a large percentage of your society and communities are violated, it leads to more violence on a national level.

Now, as Africa and the rest of the world attempt to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, it looks like most countries will prioritize public health and economic recovery over reforming security institutions. However, for African countries, security reform must be an essential aspect of all Covid-19 recovery strategy, since effective policing is just as critical to Africa’s economic recovery post-pandemic as it is to peace and stability.

Illustration: Toyo Writes

Patrick Payne is a pseudonym. The author’s name is known by Lilith.

Enjoyed this article? Become our ‘friend’ and support us!